By Stefano Riela, Lecturer and Senior Associate Research Fellow, ISPI

Since May 1, New Zealand and the European Union (EU) are connected by a free trade agreement.

The agreement:

- eliminates all tariffs on key EU exports to New Zealand such as pigmeat, wine and sparkling wine, chocolate, confectionary and biscuits;

- opens New Zealand’s services market in key sectors such as financial services, telecommunications, maritime transport and delivery services;

- ensures non-discriminatory treatment for EU investors in New Zealand and vice versa;

- improves access for EU companies to New Zealand government procurement contracts for goods, services, works and works concessions;

- facilitates data flows, predictable and transparent rules for digital trade, and a secure online environment for consumers;

- prevents unjustified data localization requirements and maintain high standards of personal data protection;

- helps small businesses export more through a dedicated chapter on small and medium enterprises;

- reduces compliance requirement and procedures to allow for a quicker flow of goods;

- protects and enforce intellectual property rights aligning NZ standards to EU ones.

The agreement also protects geographical indications (GIs), such as protected designations of origin (PDOs) and protected geographical indications (PGIs). Of the 2,146 protected European GIs, 30% are Italian, such as Valpolicella, Chianti, Grappa, Asiago, San Daniele Ham, and Parma Ham. The agreement will also protect New Zealand GIs, such as wines and spirits, including Central Otago, Marlborough, Martinborough, Matakana, and Waiheke Island.

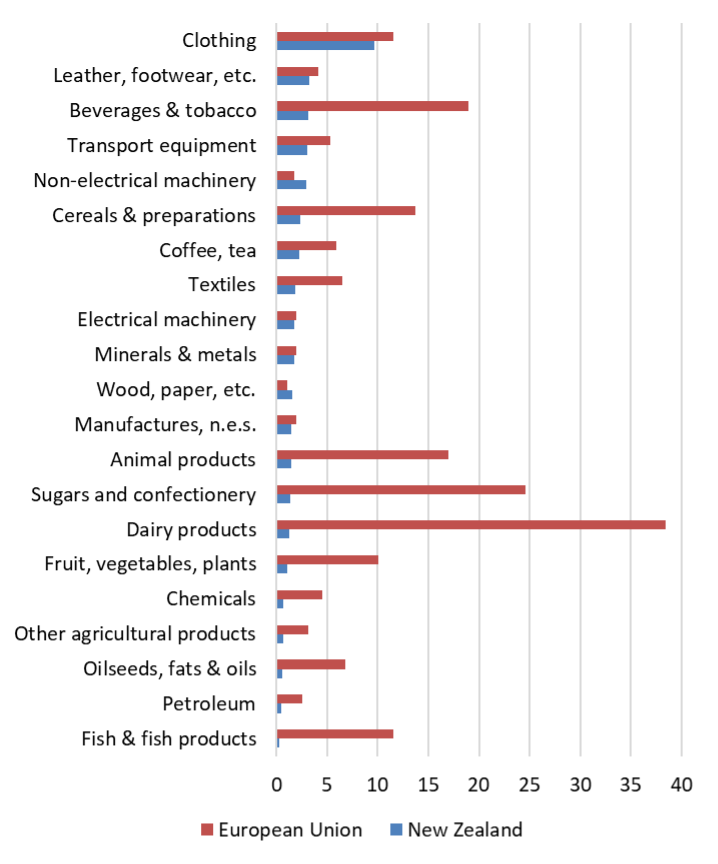

As far as trade in goods is concerned, the expected impact of this agreement does not appear to be significant, especially for the EU. New Zealand was applying lower tariffs on imports from the EU compared to the EU’s on imports from New Zealand (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Average applied tariffs before the free trade agreement (percentage)

Source: WTO

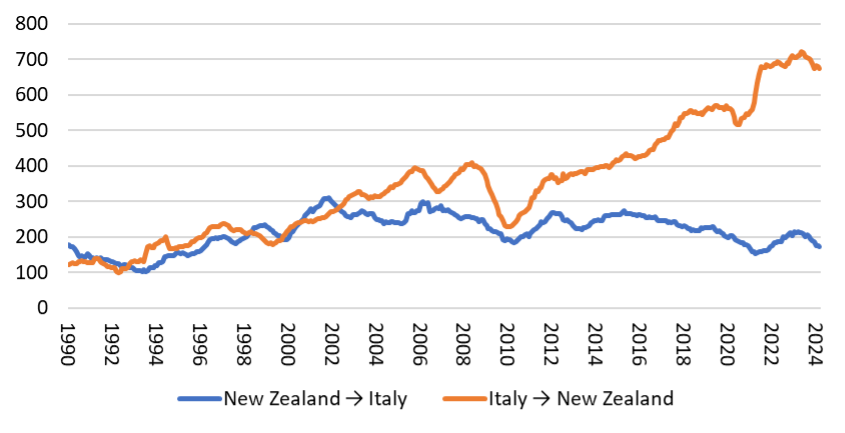

Moreover, New Zealand represents 0.16% of EU trade (2023), while the EU represents almost 10% of New Zealand and is the third largest market for its exports after China and the United States (2022). Annual trade between New Zealand and Italy reached 846.4 million EUR (ca. 1,500 million NZD) in March 2024: 673.4 million EUR of Italy’s exports to NZ and 173.0 vice versa (Figure 2) and a trade surplus for Italy equal to 500.4 million EUR.

Figure 2 – New Zealand – Italy trade (12-month value in million EUR)

Source: Eurostat

The importance of agriculture

Analyzing the type of bilateral trade, while the EU has a more balanced export to New Zealand with a prevalence of means of transport (35% in 2023), New Zealand’s export to the EU is strongly concentrated on products from agriculture (68% in 2023).

Furthermore, if you look within the macro-category “agriculture” and isolate some products you can see how New Zealand has dominated extra-EU imports thanks to a preferential regime that already existed before the agreement. For example, in 2023, 37% of the sheep meat imported by the EU came from New Zealand; 27% in the case of butter; these are significant numbers given the size of New Zealand and the geographical distance between the two trade partners.

Although in NZ the weight of the primary sector on the GDP has decreased over the years to just over 5%, the weight of the country’s exports is over 70% in value. The dairy industry, for example, dominated by Fonterra, represents around 3% of New Zealand’s GDP and 20% of its total exports. New Zealand is so efficient in this sector that, to safeguard European farmers’ interests, the EU imposed the maintenance of quotas (i.e., maximum quantities of imports per year) for meat and dairy products from New Zealand.

The political weight of the agreement

Compared to the timing of international agreements of a similar nature, the one between the EU and New Zealand was negotiated quite quickly. The final agreement, on 30 June 2022, was reached just four years after the opening of negotiations. The limited economic scope may have facilitated the negotiations even if “agriculture” represented a non-marginal element of conflict; Emmanuel Macron had requested the suspension of the negotiations during the presidential campaign for his second mandate to cool the farmers’ opposition in France.

However, the agreement is also filled with political significance in a scenario dominated by rivalries with growing effects of economic fragmentation. The EU has therefore given priority to international agreements (in addition to the negotiations with New Zealand, those with Australia were also carried out) to signal its diversity towards American protectionism during the Trump Presidency and to strengthen relations with countries considered ‘friends’ at the time of the friend-shoring proposed during President Biden following the Russian invasion in Ukraine and in light of an increasingly assertive Chinese foreign policy, especially in the South Pacific area.